LIVING GODS WILL

BIBLICAL PEOPLE

BIBLICAL PEOPLE

Click a Person to view their story

Aaron’s parents were Amram and Jochebed. He had a brother, Moses, and a sister, Miriam. When he was grown he had a family of his own. His wife’s name was Elisheba and his sons were: Eleazar, Ithamar, Nadab and Abihu.

Nadab and Abihu were struck dead by God when they offered strange fire in the role of priests. Eleazar and Ithamar took their place as priests and did a good job.

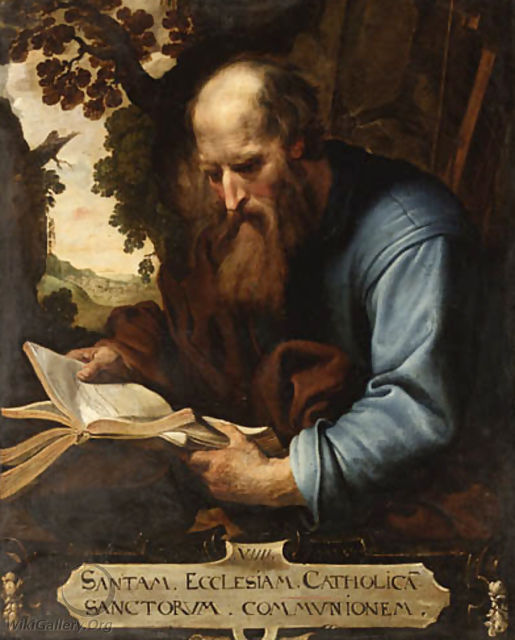

Aaron is known for his role as the first high priest. In Old Testament times, the high priest was the one that represented people before God. We also know that before he was high priest. Aaron was the spokesman for his brother, Moses.

God knew that Aaron could ‘speak well’ and Moses was ‘slow of speech’. So Aaron spoke for Moses when they represented God before Pharaoh. Aaron also performed many miracles with Moses that we read about in the book of Exodus.

Aaron was 83 years old when he and Moses spoke for God to Pharaoh. They told him that God wanted his people, the Israelites, to be freed from Egypt so that they could worship God in the desert.

Pharaoh would not listen and many plagues, showing God’s power, came upon his land until he finally let God’s people go. These are referred to as the 10 plagues.

Once the Israelites were free from Egypt, they wandered in the desert for 40 years. Aaron was their high priest during this time. Although Aaron was a good man, he made some bad choices that made God angry such as making a golden calf, an idol, for the people to worship while Moses was on Mount Sinai.

He also shared in Moses’ sin at Merbah when Moses struck a rock to get water for the people instead of speaking to the rock as he had been commanded by God.

Aaron died on Mount Hor. His robes, which the high priest wore, were taken and given to his son, Eleazar, who became the next high priest. Moses, his brother, and Eleazar, his son, were present at his death and buried him. The entire Israelite community mourned his death for 30 days.

Abel is Eve’s second son. Abel became a herder of sheep while Cain was a tiller of the soil. And it happened in the course of time that Cain brought from the fruit of the soil an offering to the Lord.

And Abel too had brought from the choice firstlings of his flock, and the Lord regarded Abel and his offering but did not regard Cain and his offering. And Cain was very incensed, and his face fell.

And the Lord said to Cain, “Why are you incensed, and why is your face fallen? For whether you offer well, or whether you do not, at the tent flap sin crouches and for you is its longing, but you will rule over it.”

And Cain said to Abel his brother, “Let us go out to the field,” and when they were in the field Cain rose against Abel his brother and killed him. And the Lord said to Cain, “Where is Abel your brother? And he said, “I do not know: am I my brother’s keeper?”.

Abimelech (also spelled Abimelek), one of Gideon’s sons, served as a judge of Israel following the judgeship of Gideon. He is first mentioned in Judges 8:30–31 where we read, “[Gideon] had seventy sons of his own, for he had many wives. His concubine, who lived in Shechem, also bore him a son, whom he named Abimelek.”

Gideon was of the tribe of Manasseh and had led Israel to victory despite humanly impossible odds. After this victory, he became wealthy and had several wives, including a concubine in Shechem who became the mother of Abimelech.

Abimelech sought to rule over Shechem by eliminating all his opposition—namely, by killing all of the other sons of Gideon. All were killed except Gideon’s youngest son, Jotham. Abimelech then became king of Shechem.

After leading Shechem for three years, a conspiracy arose against Abimelech. Civil war broke out, leading to a battle at a town called Thebez. Abimelech cornered the leaders of the city in a tower and came near with the intention of burning the tower with fire.

The text then notes, “A woman [in the tower] dropped an upper millstone on [Abimelech’s] head and cracked his skull. Hurriedly he called to his armor-bearer, Draw your sword and kill me, so that they can’t say, A woman killed him. So his servant ran him through, and he died. When the Israelites saw that Abimelek was dead, they went home.

An “upper millstone” was a large rock approximately 18 inches in diameter, and this is what landed on Abimelech’s head. Though he survived the crushing blow, Abimelech knew he would not live long.

He commanded his young armor-bearer to finish him off for the sake of his reputation (a practice seen in other places in the Old Testament). The young man did as commanded, and the battle ended in the defeat of Abimelech’s forces.

Abner is initially mentioned incidentally in Saul’s history, first appearing as the son of Ner, Saul’s uncle, and the commander of Saul’s army. He then comes to the story again as the commander who introduced David to Saul following David’s killing of Goliath.

He is not mentioned in the account of the disastrous battle of Gilboa when Saul’s power was crushed. Seizing the youngest but only surviving of Saul’s sons, Ish-Bosheth, Abner set him up as king over Israel at Mahanaim, east of the Jordan.

David, who was accepted as king by Judah alone, was meanwhile reigning at Hebron, and for some time war was carried on between the two parties.

The only engagement between the rival factions which is told at length is noteworthy, inasmuch as it was preceded by an encounter at Gibeon between twelve chosen men from each side, in which the whole twenty-four seem to have perished.

In the general engagement which followed, Abner was defeated and put to flight. He was closely pursued by Asahel, brother of Joab, who is said to have been “light of foot as a wild roe”. As Asahel would not desist from the pursuit, though warned, Abner was compelled to slay him in self-defense.

This originated a deadly feud between the leaders of the opposite parties, for Joab, as next of kin to Asahel, was by the law and custom of the country the avenger of his blood. This battle was part of a civil war between David and Ish-Bosheth, the son of Saul.

After this battle Abner switched to the side of David and granted him control over the tribe of Benjamin. This act put Abner in David’s favor. The real reason that Joab killed Abner was that he became a threat to his rank of general. He then justifies it later by mentioning his brother.

For some time afterward the war was carried on, the advantage being invariably on the side of David. At length, Ish-Bosheth lost the main prop of his tottering cause by accusing Abner of sleeping with Rizpah, one of Saul’s concubines, an alliance which, according to contemporary notions, would imply pretensions to the throne.

Abner was indignant at the rebuke, and immediately opened negotiations with David, who welcomed him on the condition that his wife Michal should be restored to him. This was done, and the proceedings were ratified by a feast.

Almost immediately after, however, Joab, who had been sent away, perhaps intentionally returned and slew Abner at the gate of Hebron. The ostensible motive for the assassination was a desire to avenge Asahel, and this would be a sufficient justification for the deed according to the moral standard of the time.

The conduct of David after the event was such as to show that he had no complicity in the act, though he could not venture to punish its perpetrators. And David said to all the people who were with him, Rend your clothes and gird yourselves with sackcloth, and wail before Abner.

And King David went after the bier. And they buried Abner in Hebron, and the king raised his voice and wept on Abner’s grave, and all the people wept. Shortly after Abner’s death, Ish-Bosheth was assassinated as he slept, and David became king of the reunited kingdoms.

Absalom was the third son of King David, by his wife Maacah. The bulk of Absalom’s story is told in 2 Samuel 13-19. He had a strong influence on his father’s reign.

The first recorded event defining Absalom’s life also involved his sister Tamar and half-brother Amnon. Tamar was beautiful, and Amnon lusted after her. When Tamar rebuffed Amnon’s advances, he arranged, through subterfuge, to have her come to his house, where he raped her. After the rape, Amnon put Tamar out of his house in disgrace.

When Absalom heard what happened, he took his sister in to live with him. For the next two years, Absalom nursed a hatred of his half-brother. Then, using some subterfuge of his own, Absalom invited Amnon to his house for a party. During the festivities, in the presence of David’s other sons, Absalom had his servants kill Amnon in cold blood.

Out of fear of his father, Absalom ran away to Geshur, where he stayed for three years. During that time, Scripture says that David “longed to go out to Absalom,” but we’re never told that he actually did anything to reconcile the relationship.

David’s general, Joab, was ultimately responsible for bringing Absalom back to Jerusalem. However, even then, Absalom was not permitted to enter David’s presence, but had to live in a house of his own. He lived this way, presumably never contacting or being contacted by his father, for two years. Finally, once again by way of Joab’s intercession, the two men get back together, and there is a small measure of reconciliation.

Unfortunately, this peace did not last. Possibly resenting his father’s hesitancy to bring him home, Absalom began to stealthily undermine David’s rule. He set himself up as judge in Jerusalem and gave out promises of what he would do if he were king. After four years of this, he asked to go to Hebron, where he had secretly arranged to have himself proclaimed king.

The conspiracy strengthened, and the number of Absalom’s followers grew steadily, such that David began to fear for his own life. David gathered his servants and fled Jerusalem. However, David left behind some of his concubines and a few informers as well, including Zadok and Abiathar the priests and his advisor Hushai.

Upon entering Jerusalem as king, Absalom sought to solidify his position, first by taking over David’s house and sleeping with his concubines, considered an unforgiveable act. Then he laid plans to immediately pursue and attack David’s forces, but the idea was abandoned owing to the advice of Hushai.

This delay allowed David to muster what troops he had at Mahanaim and mount a counterattack to retake the kingdom. David himself did not take part in the counterattack, having been persuaded by his generals to remain behind. He did give explicit instructions to the generals to “deal gently” with Absalom, in spite of his treason.

Scripture makes the point that all the troops heard David’s orders concerning Absalom. However, the orders were disobeyed. As Absalom was riding under some trees, his long hair became entangled in the branches, and he was unhorsed. Joab found Absalom suspended in mid-air and killed him there. Thus, the rebellion was quelled, and David returned to Jerusalem as king.

David mourned deeply over his son, so much so that it affected the morale of the army. His grief was so great that their victory seemed hollow to them, and they returned to the capital in shame rather than triumph. It was not until he was rebuked by Joab that David was restored to a measure of kingly behavior.

Originally called Abram, “exalted father”. Son of Terah, born in Ur of the Chaldees. The migration to Haran, where Terah died. Abraham’s journey to Canaan, the divine call, and the covenant. His sojourn in Egypt.

Other important events: settlement in Hebron; rescue of Lot and the meeting with Melchizedek; institution of circumcision and change of name to Abraham; intercession for Lot at Sodom; offering of Isaac and renewal of the covenant and blessings; death of Sarah and purchase of the cave of Machpelah as a family burial place. He lived 175 years.

The story of Achan is found in Joshua 7. God had delivered Jericho into the Israelites’ hands, as recorded in Joshua 6. The Israelites had been instructed to destroy everything in the city, with the exception of Rahab and her family, as well as the city’s gold, silver, bronze, and iron.

The metals were to go into the tabernacle treasury; they were “sacred to the Lord” or “devoted” to Him. Jericho was to be totally destroyed, and the Israelites were to take no plunder for themselves.

Shortly after their success at Jericho, the Israelites moved on to attack the city of Ai. The spies Joshua sent to Ai thought the city would be easy to overtake—much easier than Jericho—and they suggested Joshua only send two or three thousand troops.

Much to their shock, the Israelites were chased out of Ai, and thirty-six of them were killed. Joshua tore his clothes and bemoaned their attempts at conquering Canaan.

He told God, “The Canaanites and the other people of the country will hear about this and they will surround us and wipe out our name from the earth. What then will you do for your own great name?”. God responded by telling Joshua that some Israelites had sinned by taking devoted things. The people were to consecrate themselves, and then the following morning the perpetrator would be identified by lot.

When morning came, each tribe presented itself. The tribe of Judah was chosen by lot, then the clan of the Zerahites, then the family of Zimri, then Achan. “Then Joshua said to Achan, ‘My son, give glory to the Lord, the God of Israel, and honor him. Tell me what you have done; do not hide it from me’”.

Achan confessed his sin, admitting that in Jericho he saw a robe, two hundred shekels of silver, and a fifity-shekel bar of gold that he “coveted,” took, and hid in a hole he had dug within his tent. Messengers from Joshua confirmed the plunder was found in Achan’s tent, and they brought it before the assembly.

The Israelites then stoned Achan, his children, and his livestock and burned the bodies; they also burned Achan’s tent, the plunder he had taken, and “all that he had” in the Valley of Achor (i.e., the “Valley of Trouble”). The pile of stones was left there as a reminder of Achan’s sin and the high cost of not obeying the Lord.

After Achan was judged, God told Joshua, “Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged. Take the whole army with you, and go up and attack Ai. For I have delivered into your hands the king of Ai, his people, his city and his land”.

The Israelites laid an ambush and soundly defeated Ai, killing all of its inhabitants. This time, the Israelites were allowed to take the plunder for themselves. Only Jericho, the first city in Canaan, had been wholly devoted to the Lord.

The story of Achan is a stark reminder of the penalty of sin, which is death. We also see two truths illustrated plainly: first, that sin is never an isolated event—our sin always has a ripple effect that touches others.

Achan’s sin led to the deaths of thirty-six of his fellow soldiers and defeat for the whole army. Second, we can always be sure that our sins will find us out. Hiding the evidence in our tents will not conceal it from God.

Achan’s sin was grave. He took what was God’s. The Israelites had been specifically warned about the consequences of not doing as God instructed. Joshua told them, “Keep away from the devoted things, so that you will not bring about your own destruction by taking any of them. Otherwise you will make the camp of Israel liable to destruction and bring trouble on it”.

Achan’s sin was a clear and willful violation of a direct order, and he did bring trouble on the entire camp of Israel. Also, Achan was given time to repent on his own; he could have come forward at any time, yet chose to wait through the casting of lots.

Rather than admit his guilt and perhaps call on the mercy of God or at least demonstrate reverence for Him, Achan attempted to hide. “Whoever conceals their sins does not prosper, but the one who confesses and renounces them finds mercy”.

The first man created on earth. Adam is the father and patriarch of the human race on the earth.

His transgression in the Garden of Eden caused him to “fall” and become mortal, a step necessary in order for mankind to progress on this earth. Adam and Eve should therefore be honored for their role in making our eternal growth possible.

God created man in his own image. God gave man dominion over all things and commanded him to multiply and fill the earth. God placed Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and forbade them to eat of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. Adam named every living creature.

Adam and Eve were married by God. Adam and Eve were tempted by Satan, partook of the forbidden fruit, and were cast out of the Garden of Eden. Adam was 930 years old at his death.

After the death of his elder brothers Amnon and Absalom, Adonijah considered himself the heir-apparent to the throne. He acquired chariots and a large entourage. Although the king was aware of this, he neither rebuked his son nor made any inquiry into his actions.

David’s silence may have been interpreted by Adonijah and others as consent. Adonijah consulted and obtained the support of both the commander of the army Joab and the influential priest Abiathar. However, the priest Zadok; Benaiah, head of the king’s bodyguard; Nathan, the court prophet; and others did not side with Adonijah.

In anticipation of his father’s imminent death, Adonijah invited his brother princes and the court officials to a solemn sacrifice in order to announce his claim to the throne. He did not invite Solomon or any of his supporters.

Assuming that Adonijah will soon move to eliminate any rivals or opposition, Nathan warns Bathsheba, Solomon’s mother, and counsels her to remind the king of a previous promise to make Solomon his successor.

However, Adonijah was supplanted by Solomon through the influence of Bathsheba, and through the diplomacy of the prophet Nathan. They induced David to give orders that Solomon should immediately be proclaimed and admitted to the throne.

Adonijah fled and took refuge at the altar, receiving pardon for his conduct from Solomon on the condition that he showed himself a worthy man. He afterwards made a second attempt to gain the throne, by trying to marry David’s last woman, Abishag from Shunem, but Solomon denied authorization for such an engagement, even though Bathsheba now pleaded on Adonijah’s behalf. He was then put to death.

Most commentators believe Agur lived in the same era as Solomon. We don’t know much about Agur except what we can glean from this one chapter.

The name Agur comes from a Hebrew word meaning “collector.” Agur and Jakeh are only mentioned here in the Bible and are otherwise unknown.

Agur’s proverbs offer insight regarding his thoughts on life. Agur was weary and worn out, he did not consider himself wise, and he considered God’s words completely true.

In Proverbs 30 Agur expresses to God a request that the Lord remove lying from him and give him neither riches nor poverty.

Agur’s teachings include a warning not to slander servants and an observation that many people see themselves as better than they really are. Agur then begins a numbered list of sayings that includes three things never satisfied the barren womb, the land’s need for water, and the end of a fire. Verse 17 adds that the person who mocks his parents will experience judgment.

Verses 18–19 list four things beyond Agur’s understanding: an eagle in the sky, a serpent on a rock, a ship on the seas, and a man with a woman.

In verses 21–23 is a list of four things that cause the earth to tremble: a slave who becomes king, a well-fed fool, an unloved married woman, and a servant who replaces the wife in the household.

Verses 24–28 note four small things that are very wise: ants, rock badgers, locusts, and lizards. Verses 29–31 specify four proud things: a lion, a rooster, a goat, and a king with his army. Verses 32–33 advise that, if you have been foolish in exalting yourself, you need to stop; also, prodding someone to anger is unwise.

These simple yet profound observations on life reveal many aspects of this otherwise unknown man named Agur. For example, Agur realized God’s wisdom was greater than his own. He understood the temptation of riches. He knew many aspects of life and of God’s creation would remain a mystery beyond his understanding.

And Agur knew the importance of controlling anger, avoiding foolishness, and living for God. He encourages his readers to refrain from a life that dishonors God and results in judgment. Rather, Agur promotes living life with a proper fear of God and concern for other people.

Ahab was one in a line of increasingly evil kings in Israel’s history, starting with the reign of Jeroboam. King Ahab “did more evil in the eyes of the LORD than any of those before him”.

Among the events chronicled in Ahab’s life that led to his downfall was his marriage to an evil woman named Jezebel who had a particular hatred for God’s people. Because of his marriage to a pagan woman, Ahab devoted himself to the worship of the false gods Baal and Asherah in Israel.

The evil of King Ahab was countered by the prophet Elijah who warned Ahab of coming judgment if he did not obey the Lord. Ahab blamed Elijah for bringing trouble on Israel, but it was Ahab’s promotion of idolatry that was the true cause of the three-and-a-half-year famine. In a dramatic confrontation between Elijah and Ahab’s false prophets, God proved to Israel that He, not Baal, was the true God. All of Ahab’s men of Baal were killed that day.

King Ahab also disobeyed the Lord’s direct command to destroy Ben-Hadad, the king of Aram. God set it up so that Ahab would lead Israel to victory, but Ahab made a treaty with the king he was supposed to kill. Therefore, God told Ahab through an unnamed prophet, “it is your life for his life, your people for his people”.

The event that sealed Ahab’s doom was his murder of an innocent man. Ahab coveted a vineyard belonging to a man named Naboth. The king offered to buy the vineyard, but Naboth refused, because the Law forbade him to sell it.

While Ahab sulked about it in his palace, his wife arranged Naboth’s murder. Once the vineyard’s owner was out of the way, King Ahab took the vineyard for himself.

Elijah came to Ahab and told him the Lord would deal with him by cutting off all his descendants. Also, Ahab himself would suffer an ignoble fate: “In the place where dogs licked up Naboth’s blood, dogs will lick up your blood—yes, yours!”.

Upon hearing this, Ahab “tore his clothes, put on sackcloth and fasted. He lay in sackcloth and went around meekly”. In response to Ahab’s repentance, God mercifully postponed the destruction of Ahab’s dynasty until after Ahab was dead.

The prophesied judgment against Ahab came true exactly as Elijah predicted. God used Ahab’s own false prophets to entice him into going to the battle at Ramoth-Gilead, where he was hit by a “random” arrow and slowly bled to death in his chariot.

Later, “they washed the chariot at a pool in Samaria (where the prostitutes bathed), and the dogs licked up his blood, as the word of the Lord had declared”. After Ahab’s death, Jehu killed Jezebel and all of Ahab’s descendants.

The name Xerxes does not appear in the Hebrew text of Scripture. In the Hebrew text, the king’s name is Ahasuerus. Nothing is known of a king named Ahasuerus from secular sources, and the names of all the Persian kings from this time period are known.

Most commentators equate Esther’s king with Xerxes I (485–465 BC), son of Darius I, the fourth emperor of the Achaemenid Empire—thus the translation in some modern versions. (There is some evidence to show that the Hebrew name Ahasuerus can be easily derived from the Persian name.)

The Septuagint (Greek translation of the Old Testament) uses the name Artaxerxes, which further complicates the issue, for there were two Persian rulers by that name: Artaxerxes I (465–424 BC) and Artaxerxes II (404–359 BC).

What we know of the character of Xerxes I fits with what we see in the book of Esther. Xerxes had a summer palace in Susa. He was known for his drinking, lavish banquets, harsh temper, and sexual appetite.

Esther mentions a foiled plot against his life, and we know from secular history that, later, in 465, Xerxes was assassinated by the head of his bodyguard.

The most likely scenario is that the episode of Xerxes’ life involving Esther took place after Xerxes’ disastrous invasion of Greece in 480 BC. Xerxes’ forces paid a heavy toll at the pass of Thermopylae at the hands of the fabled 300 Spartans and were defeated at Salamis. Returning home, Xerxes turned to domestic affairs.

King Ahasuerus (Xerxes) plays a prominent role in the book of Esther. In chapter 1 he gives a great banquet for his nobles and, after several days of eating and drinking, orders that the queen Vashti appear at the banquet so the men there might see her great beauty. Vashti refuses to attend, so the king deposes her.

Xerxes begins to regret his decision to oust the queen, and he decides to find a new queen. The queen of Persia was not simply the wife of the king. The queenship was an honorary/political position.

The king was a polygamist with many wives and concubines in his harem, but the queen was a special wife occupying a favored position. A call is sent out throughout the kingdom for all beautiful virgins to be gathered into the harem so that the king could choose a new queen from among them.

As a member of the harem, a woman would technically be the property of the king—either a wife or a concubine. Each of the women would spend a night with the king. After their night together, each woman would be moved to the “other side” of the harem and would never see the king again, unless he called for her.

When he found the “right one,” Xerxes would name her queen, although she would not be his exclusive wife or sexual partner. A woman whom Xerxes never called again would live her life in the harem as a pampered prisoner with no possibility for a real marriage or family of her own.

A Jewess named Esther, who was raised by her cousin Mordecai, was one of the women rounded up for Xerxes. She was eventually named queen, but she kept her nationality a secret. Mordecai is anxious for Esther and loiters day after day near the harem quarters to monitor how she is doing. In so doing, he overhears a plot to kill the king. He reports it to Esther, who reports it to the king, and the plot is foiled.

One of Xerxes’ chief advisors, Haman, is angered that Mordecai will not bow down to him, so he hatches a plot to kill not only Mordecai but all of the Jews. Haman convinces King Xerxes to authorize the extermination; however, it appears that the king does not know the identity of the people that Haman plans to wipe out—only that they are enemies of the state.

He trusts Haman to handle the details. Mordecai informs Esther of the danger the Jews are in and convinces her to intercede with the king. The problem Esther faces is that Xerxes has not called for her for some time and, if she approaches him without being summoned, she risks death.

At this point, neither the king nor Haman knows Esther’s nationality or her relationship to Mordecai.

Mordecai encourages Esther to take the risk, saying that perhaps she has been made queen “for such a time as this”.

The queen approaches Xerxes, and he extends his scepter to her, signifying that he welcomes her into his presence. Instead of explaining her predicament, however, Esther invites the king and Haman to a private banquet.

At the banquet Esther again puts off addressing the issue; instead, she asks the king and Haman to come to another banquet the next day, which they agree to do. Haman is so overjoyed and emboldened by the special attention he’s receiving from the queen that he decides to have Mordecai hanged in advance of the general slaughter of the Jews.

The king cannot sleep, so he has the royal annals read to him. When the account of the foiled plot against his life is recounted, Xerxes asks if Mordecai has ever been honored for saving him. When he finds that Mordecai has never been rewarded, Xerxes decides to remedy the oversight.

At that moment, Haman enters, and the king asks him, What should be done to the man whom the king delights to honor? Haman thinks the king is referring to him, so he proposes a lavish public display: For the man whom the king delights to honor, let royal robes be brought, which the king has worn, and the horse that the king has ridden, and on whose head a royal crown is set.

And let the robes and the horse be handed over to one of the king’s most noble officials. Let them dress the man whom the king delights to honor, and let them lead him on the horse through the square of the city, proclaiming before him: Thus shall it be done to the man whom the king delights to honor.

The king thinks it is a splendid idea to be carried out immediately and tells Haman, Hurry; take the robes and the horse, as you have said, and do so to Mordecai the Jew, who sits at the king’s gate. Leave out nothing that you have mentioned.

So, in what some would call a strange “twist of fate,” Haman has to publicly honor Mordecai. After his humiliation, Haman hurriedly prepares for the banquet with Esther and the king, as Haman’s family laments that certainly fate is against him now.

At the second banquet, Xerxes asks Esther, What is your wish, Queen Esther? It shall be granted you. And what is your request? Even to the half of my kingdom, it shall be fulfilled. Esther begs for the life of herself and her people.

The king is enraged and asks who would dare plot such a thing. Esther answers, “A foe and enemy! This wicked Haman! The king rushes from the room in a rage, and Haman throws himself upon the couch where Esther is reclining to plead for his life.

At that moment, the king returns and misinterprets Haman’s actions: Will he even assault the queen in my presence, in my own house? Haman is whisked away and hanged on the very gallows he had prepared for Mordecai.

The house of Haman is given to Esther, and his position in the court is given to Mordecai.

Even though Haman is out of the way, the plot to kill all the Jews is still afoot. It appears that the king’s edict called for citizens of Persia to kill Jews on a certain day and confiscate their property.

The edict, which could not be rescinded, is modified to allow the Jews to defend themselves, and in chapter 9 they are able to withstand the attack, and many of their enemies are killed.

God is not mentioned in the book of Esther, but He is conspicuous by His absence. In Esther we do not see any miracles or divine intervention. However, we do see an abundance of providence, which is God’s control and provision through “natural” means.

It is clear that the writer of the book intends us to see God’s unseen hand behind every detail and ironic twist of “fate.” Although Xerxes is the king, he is not ultimately in charge. The king of Persia is little more than a bit player in God’s all-encompassing drama.

Was king of Judah, and the son and successor of Jotham. Ahaz was 20 when he became king of Judah and reigned for 16 years. Ahaz is portrayed as an evil king in the Book of Kings.

Edwin R. Thiele concluded that Ahaz was coregent with Jotham from 736/735 BC, and that his sole reign began in 732/731 and ended in 716/715 BC. The Gospel of Matthew lists Ahaz of Judah in the genealogy of Jesus. He is also mentioned in the book of Isaiah.

Ahaz’s reign commenced at the age of 20, in the 17th year of the reign of Pekah of Israel. Immediately upon his accession Ahaz had to meet a coalition formed by northern Israel, under Pekah, and Damascus (Syria), under Rezin.

These kings wished to compel him to join them in opposing the Assyrians, who were arming a force against the Northern Kingdom under Tiglath-Pileser III. (Pul). To protect himself Ahaz called in the aid of the Assyrians. Tiglath-Pileser sacked Damascus and annexed Aram.

According to 2 Kings, the population of Aram was deported and Rezin executed. Tiglath-Pileser then attacked Israel and took Ijon, Abel Beth Maacah, Janoah, Kedesh and Hazor. He took Gilead and Galilee, including all the land of Naphtali, and deported the people to Assyria. Tiglath-Pileser also records this act in one of his inscriptions.

Through Assyria’s intervention, and as a result of its invasion and subjection of the kingdom of Damascus and the Kingdom of Israel, Ahaz was relieved of his troublesome neighbors; but his protector henceforth claimed and held suzerainty over his kingdom.

This war of invasion lasted two years (734-732 BC), and ended in the capture and annexation of Damascus to Assyria and of the territory of Israel north of the border of Jezreel.

Ahaz in the meanwhile furnished auxiliaries to Tiglath-Pileser. This appeal to Assyria met with stern opposition from the prophet Isaiah, who counseled Ahaz to rely upon the Lord and not upon outside aid. The sequel seemed to justify the king and to condemn the prophet.

Ahaz, during his whole reign, was free from troubles with which the neighboring rulers were harassed, who from time to time revolted against Assyria.

Thus it was that, in 722, Samaria was taken and northern Israel wholly incorporated into the Assyrian empire.

Ahaz, who was irresolute and impressionable, yielded readily to the glamour and prestige of the Assyrians in religion as well as in politics. In 732 he went to Damascus to swear homage to Tiglath-Pileser and his gods; and, taking a fancy to an altar which he saw there, he had one like it made in Jerusalem, which, with a corresponding change in ritual, he made a permanent feature of the Temple worship.

Changes were also made in the arrangements and furniture of the Temple, “because of the king of Assyria”. Furthermore, Ahaz fitted up an astrological observatory with accompanying sacrifices, after the fashion of the ruling people. In other ways Ahaz lowered the character of the national worship. It is recorded that he even offered his son by fire to Moloch.

His government is considered by the Deuteronomistic historian, as having been disastrous to the religious state of the country; and a large part of the reforming work of his son Hezekiah was aimed at undoing the evil that Ahaz had done.

He died at the age of 36 and was succeeded by his son, Hezekiah. Because of his wickedness he was not brought into the sepulcher of the kings.

An insight into Ahaz’s neglect of the worship of the Lord is found in the statement that on the first day of the month of Nisan that followed Ahaz’s death, his son Hezekiah commissioned the priests and Levites to open and repair the doors of the Temple and to remove the defilements of the sanctuary, a task which took 16 days.

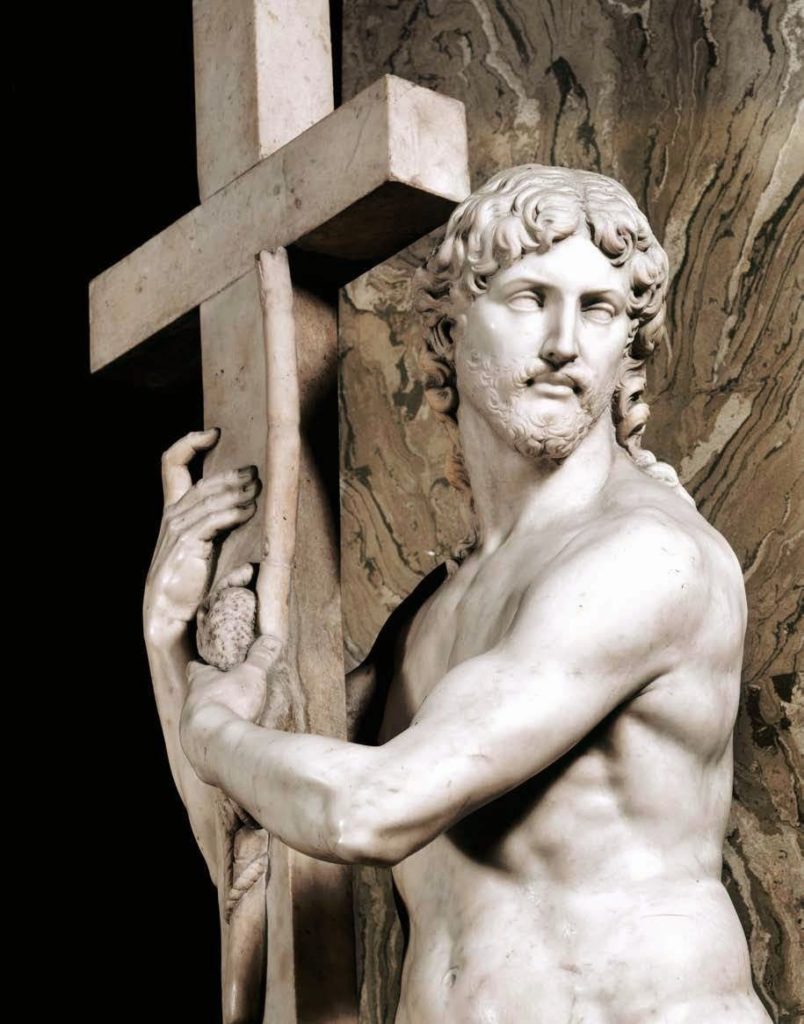

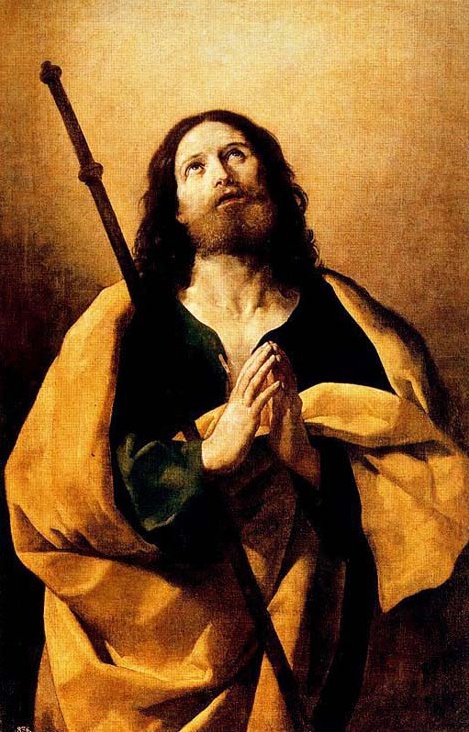

(Peter’s brother) (Fisherman) Brother of Simon Peter. As a disciple of John the Baptist he met Jesus and then brought Peter to meet Jesus. He was one of the earliest called to be a disciple of Jesus Christ and was one of the Twelve. The Apostle was Crucified on an X-shaped Cross, the two ends of which were in the ground.

The sordid story of Amnon and Tamar is part of the disintegration of David’s family after his sin with Bathsheba. Amnon was the half-brother of Tamar, as they shared the same father, David.

Tamar is described as a virgin and “beautiful,” and Amnon was highly attracted to her. Amnon did not know what to do about his infatuation, and he soon confided in a friend named Jonadab.

Jonadab was “very shrewd” and gave Amnon a plan, saying, Go to bed and pretend to be ill. When your father comes to see you, say to him, I would like my sister Tamar to come and give me something to eat. Let her prepare the food in my sight so I may watch her and then eat it from her hand.

The idea was to get Amnon and Tamar alone together, and then Amnon could do as he pleased. Amnon followed this evil plan. He asked for his half-sister to bring him some food, and Tamar, out of obedience to her father and the kindness of her heart, did so.

Amnon sent everyone else out of the room and asked Tamar to come closer. Rather than take the food she offered, Amnon grabbed Tamar and tried to wrestle her into the bed. Tamar firmly refused the incestuous relationship, crying out, No, my brother! Don’t do this wicked thing. Amnon then forced himself upon Tamar and raped her.

Afterwards, Amnon was said to hate Tamar more than he had loved her before the rape occurred. It was never really love at all, but brazen lust. Absalom, Tamar’s full-brother, found out about the deed, and so did David. David’s response was to become furious, but he took no real action.

Absalom cared for Tamar in his own home and would not speak to Amnon. Two years later Absalom commanded his servants to murder Amnon in revenge. Absalom fled the country for a time and later returned to David.

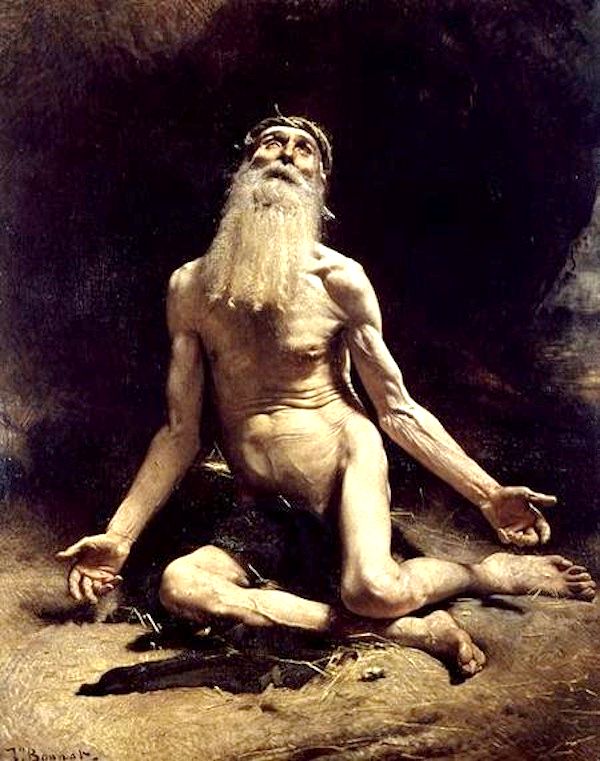

Was one of the Twelve Minor Prophets. An older contemporary of Hosea and Isaiah, Amos was active c. 760–755 BCE during the reign of Jeroboam II (786–746 BCE). He was from the southern Kingdom of Judah but preached in the northern Kingdom of Israel.

Amos wrote at a time of relative peace and prosperity but also of neglect of GOD’s laws. He spoke against an increased disparity between the very wealthy and the very poor. His major themes of social justice, God’s omnipotence, and divine judgment became staples of prophecy. The Book of Amos is attributed to him.

Before becoming a prophet, Amos was a sheep herder and a sycamore fig farmer. Amos’ prior professions and his claim I am not a prophet nor a son of a prophet indicate that Amos was not from the school of prophets, which Amos claims makes him a true prophet.

Amos’ declaration marks a turning-point in the development of Old Testament prophecy. It is not mere chance that Hosea, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and almost all of the prophets who are more than unknown personages to whom a few prophetical speeches are ascribed, give first of all the story of their special calling.

All of them thereby seek to protest against the suspicion that they are professional prophets, because the latter discredited themselves by flattering national vanities and ignoring the misdeeds of prominent men.

The Bible speaks of his ministry and prophecies concluding around 762, two years before the earthquake that is spoken of in Amos 1:1, “…two years before the earthquake.”

The prophet Zechariah likely was referencing this same earthquake several centuries later. From Zechariah 14:5, “And you shall flee as you fled from the earthquake in the days of Uzziah king of Judah.”

Despite being from the southern kingdom of Judah Amos’ prophetic message was aimed at the Northern Kingdom of Israel, particularly the cities of Samaria and Bethel.

Jeroboam II (c. 781–741 BCE), ruler of the Northern kingdom, had rapidly conquered Syria, Moab, and Ammon, and thereby extended his dominions from the source of the Orontes on the north to the Dead Sea on the south.

The whole northern empire of Solomon thus practically restored had enjoyed a long period of peace and security marked by a revival of artistic and commercial development. Social corruption and the oppression of the poor and helpless were prevalent.

Many availed themselves of the throngs which attended the sacred festivals to indulge in immoderate enjoyment and tumultuous revelry. Others, carried away by the free association with heathen peoples which resulted from conquest or commercial contact, went so far as to fuse with the Lord’s worship that of pagan deities.

Amos is the first of the prophets to write down the messages he has received. He has always been admired for the purity of his language, his beauty of diction, and his poetic art. In all these respects he is Isaiah’s spiritual progenitor.

What we know of Amos derives solely from the book that he himself authored. This makes it hard to know who the historical Amos truly was. Amos felt himself called to preach in Bethel, where there was a royal sanctuary, and there to announce the fall of the reigning dynasty and of the northern kingdom.

But he is denounced by the head priest Amaziah to King Jeroboam II and is advised to leave the kingdom. There is no reason to doubt that he was forced to leave the northern kingdom and to return to his native country.

Being thus prevented from bringing his message to an end, and from reaching the ear of those to whom he was sent, he had recourse to writing. If they could not hear his messages, they could read them, and if his contemporaries refused to do so, following generations might still profit by them.

No earlier instance of a literary prophet is known; but the example he gave was followed by others in an almost unbroken succession. It cannot be proved that Hosea knew the book of Amos, though there is no reason to doubt that he was acquainted with the latter’s work and experiences.

It is certain that Isaiah knew his book, for he follows and even imitates him in his early speeches. Cheyne concludes that Amos wrote the record of his prophetical work at Jerusalem, after his expulsion from the northern kingdom, and that he committed it to a circle of faithful followers residing there.

The apocryphal work The Lives of the Prophets records that Amos was killed by the son of Amaziah, priest of Bethel. It further states that before he died, Amos made his way back to his homeland and was buried there.

Archippus is mentioned in Colossians 4:17 and Philemon 1:2. In his letter to Philemon, Paul refers to Archippus as a fellow soldier. In Colossians 4:17, Paul requests his readers to tell Archippus:

See to it that you complete the ministry you have received in the Lord. Apparently, then, Archippus was a young man from Colossae tasked with some sort of ministry in the church. Many believe Archippus to have been the son of Philemon and Apphia, close friends of Paul’s.

The connection between Archippus and Philemon seems clear in Philemon 1:2–2, To Philemon our dear friend and fellow worker—also to Apphia our sister and Archippus our fellow soldier—and to the church that meets in your home.

Paul is writing to a household. Philemon; his wife, Apphia; and his son, Archippus comprise the family unit. The church of Colossae met in their home. Some believe Paul’s words to Archippus to complete the ministry are a gentle rebuke for having neglected certain of his duties.

But a majority see Paul’s admonition to Archippus as simple encouragement, similar to Paul’s exhortations in his epistles to Timothy and Titus. One tradition holds that Archippus was a leader in Laodicea, a city about 12 miles away from Colossae.

It seems strange to send an admonition to Archippus through leaders of another church, but Paul’s intent was that the letter to the Colossians should be read in Laodicea, too: After this letter has been read to you, see that it is also read in the church of the Laodiceans. In any case, Archippus would receive the message.

Ultimately, we do not know much about Archippus other than he was a Christian in the early church who was granted a ministry from the Lord and who soldiered for the faith.

Paul’s encouragement to Archippus and his family should encourage all of us to also complete the ministry God has given us.

Artaxerxes is described in the Bible as having commissioned Ezra, a Jewish priest and scribe, by means of a letter of decree, to take charge of the ecclesiastical and civil affairs of the Jewish nation.

Ezra thereby left Babylon in the first month of the seventh year of Artaxerxes’ reign, at the head of a company of Jews that included priests and Levites. They arrived in Jerusalem on the first day of the fifth month of the seventh year.

The rebuilding of the Jewish community in Jerusalem had begun under Cyrus the Great, who had permitted Jews held captive in Babylon to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple of Solomon.

Consequently, a number of Jews returned to Jerusalem in 538 BC, and the foundation of this “Second Temple” was laid in 536 BC, in the second year of their return. After a period of strife, the temple was finally completed in the sixth year of Darius, 516 BC.

In Artaxerxes’ 21st year (445 BC), Nehemiah, the king’s cupbearer, apparently was also a friend of the king as in that year Artaxerxes inquired after Nehemiah’s sadness. Nehemiah related to him the plight of the Jewish people and that the city of Jerusalem was undefended.

The king sent Nehemiah to Jerusalem with letters of safe passage to the governors in Trans-Euphrates, and to Asaph, keeper of the royal forests, to make beams for the citadel by the Temple and to rebuild the city walls.

Asa was a descendant of David and the third king of the southern kingdom of Judah. He ruled for forty-one years and “did what was good and right in the eyes of the Lord his God”.

Asa became king of Judah in the twentieth year of Jeroboam of Israel’s reign (Jeroboam was the first king of the northern kingdom of Israel after the kingdom divided). Asa’s father, Abijah, had done much evil in God’s sight and only ruled for three years. Asa’s grandfather, Rehoboam, had also done evil in God’s sight.

But King Asa instituted reform; he removed the male shrine prostitutes, cut down Asherah poles, and even deposed his grandmother from her position as queen mother because of her involvement with Asherah worship.

Asa also commanded his people to follow the Lord. First Kings 15:14 says, “Although he did not remove the high places, Asa’s heart was fully committed to the Lord all his life”.

Judah was at peace with surrounding nations for ten years during Asa’s reign. Second Chronicles 15 describes a time when Azariah, a prophet, told Asa that, if he sought the Lord, God would be with him. This encouraged Asa to remove idols and to repair the altar at the Lord’s temple.

He assembled the people together to sacrifice to the Lord: They entered into a covenant to seek the Lord, the God of their ancestors, with all their heart and soul. All who would not seek the Lord, the God of Israel, were to be put to death, whether small or great, man or woman.

They took an oath to the Lord with loud acclamation, with shouting and with trumpets and horns. All Judah rejoiced about the oath because they had sworn it wholeheartedly. They sought God eagerly, and he was found by them. So the Lord gave them rest on every side.

Asa built up the fortified cities, and Judah enjoyed a time of prosperity. When Zerah the Cushite marched out to make war against Judah, Asa called on God for aid. The Lord struck down the Cushites before Asa and Judah. The Cushites fled, and Asa and his army pursued them as far as Gerar. Such a great number of Cushites fell that they could not recover; they were crushed before the Lord and his forces. The men of Judah carried off a large amount of plunder.

Unfortunately, in the thirty-fifth year of Asa’s reign, he made some mistakes. When King Baasha of Israel fortified Ramah to isolate the territory of Judah, Asa made a treaty with Ben-Hadad, king of Aram. The treaty was effective in stopping Israel, and the Judahites took supplies from Ramah and built up Geba and Mizpah, but the treaty with Aram was not pleasing to God.

Hanani, the seer, visited Asa and reminded him of the way God had conquered the Cushites. He chastised Asa for relying on Ben-Hadad instead of God. Rather than repent of his sin, however, Asa became angry; he began to oppress some of his people. For the remainder of Asa’s reign, his kingdom was at war.

In the thirty-ninth year of Asa’s reign, he got a severe foot disease, but he looked only to the physicians for help and not God. In the forty-first year of his reign, Asa died and was buried with great honor.

Despite a less-than-ideal end to his reign, Asa is considered a godly and good king. His son, Jehoshaphat, succeeded him and ruled for twenty-five years. Jehoshaphat was also a godly ruler, following in his father’s footsteps and seeking the Lord, yet he also made foolish alliances with those who did not follow the Lord.

The life of King Asa is an example to all of us of how easy it is to drift away from the Lord. Asa began his reign with a strong commitment to God, but as years went by his dedication faltered, bringing unnecessary trouble.

Balaam was a wicked prophet in the Bible and is noteworthy because, although he was a wicked prophet, he was not a false prophet. That is, Balaam did hear from God, and God did give him some true prophecies to speak.

However, Balaam’s heart was not right with God, and eventually he showed his true colors by betraying Israel and leading them astray.

In Numbers we find the story about Balaam and the king of Moab, a man called Balak. King Balak wanted to weaken the children of Israel, who on their way to Canaan had moved in on his territory. Balak sent to Balaam, who lived in Mesopotamia along the Euphrates River, and asked him to curse Israel in exchange for a reward.

Balaam was apparently willing to do this but said he needed God’s permission. Balaam, of course, had no power, in himself, to curse Israel, but, if God were willing to curse Israel, Balaam would be rewarded through Balak. God told Balaam, “You must not put a curse on those people, because they are blessed”.

King Balak then sent “other officials, more numerous and more distinguished than the first”, promising a handsome reward. This time God said, “Go with them, but do only what I tell you”.

The next morning, Balaam saddled his donkey and left for Moab. God sent an angel to oppose Balaam on the way. The donkey Balaam was riding could see the angel, but Balaam could not, and when the donkey three times moved to avoid the angel, Balaam was angry and beat the animal.

“Then the Lord opened the donkey’s mouth”, and it rebuked the prophet for the beatings. “Then the Lord opened Balaam’s eyes, and he saw the angel of the Lord standing in the road with his sword drawn”.

The angel told Balaam that he certainly would have killed Balaam had not the donkey spared his life. Ironically, a dumb beast had more wisdom than God’s prophet. The angel then repeated to Balaam the instruction that he was only to speak what God told him to speak concerning the Hebrews.

In Moab, King Balak took the prophet Balaam up to a high place called Bamoth Baal and told him to curse the Israelites. Balaam first offered fourteen sacrifices on seven altars and met with the Lord.

He then declared the message God gave him: a blessing on Israel: “How can I curse those whom God has not cursed? How can I denounce those whom the Lord has not denounced?”.

King Balak was upset that Balaam had pronounced a blessing on Israel rather than a curse, but he had him try again, this time from the top of Pisgah. Balaam sacrificed another fourteen animals and met with the Lord. When he faced Israel, Balaam again spoke a blessing: “I have received a command to bless; he has blessed, and I cannot change it”.

King Balak told Balaam that, if he was going to keep blessing Israel, it was better for him to just shut up. But the king decided to try one more time, taking Balaam to the top of Peor, overlooking the wasteland. Again, Balaam offered fourteen animals on seven newly built altars.

Then “the Spirit of God came on him and he spoke his message”. The third message was not what the Moabite king wanted to hear: “How beautiful are your tents, Jacob, your dwelling places, Israel!”.

Balaam’s three prophecies of blessing on Israel infuriated the king of Moab, who told the prophet to go back home with no reward: “Now leave at once and go home! I said I would reward you handsomely, but the Lord has kept you from being rewarded”.

Before he left, Balaam reminded the king that he had said from the very beginning he could only say what God told him to say. Then he gave the king four more prophecies, gratis. In the fourth prophecy, Balaam foretold of the Messiah: “A star will come out of Jacob; a scepter will rise out of Israel.

He will crush the foreheads of Moab, the skulls of all the people of Sheth”. Balaam’s seven prophecies were seven blessings on God’s people; it was God’s enemies who were cursed.

However, later on Balaam figured out a way to get his reward from Balak. Balaam advised the Moabites on how to entice the people of Israel with prostitutes and idolatry. He could not curse Israel directly, so he came up with a plan for Israel to bring a curse upon themselves.

Balak followed Balaam’s advice, and Israel fell into sin, worshiping Baal of Peor and committing fornication with Midianite women. For this God plagued them, and 24,000 men died.

Barabbas is mentioned in all four gospels of the New Testament: His life intersects that of Christ at the trial of Jesus. Jesus was standing before Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor who had already declared Jesus innocent of anything worthy of death.

Pilate knew that Jesus was being railroaded and it was out of self-interest that the chief priests had handed Jesus over to him, so he looked for a way to release Jesus and still keep the peace.

Pilate offered the mob a choice: the release of Jesus or the release of Barabbas, a well-known criminal who had been imprisoned for an insurrection in the city, and for murder.

The release of a Jewish prisoner was customary before the feast of Passover. The Roman governor granted clemency to one criminal as an act of goodwill toward the Jews whom he governed.

The choice Pilate set before them could not have been more clear-cut: a high-profile killer and rabble-rouser who was unquestionably guilty, or a teacher and miracle-worker who was demonstrably innocent. The crowd chose Barabbas to be released.

Pilate seems to have been surprised at the crowd’s insistence that Barabbas be set free instead of Jesus. The governor stated that the charges against Jesus were baseless and appealed to the crowd three times to choose sensibly.

But with loud shouts they insistently demanded that he be crucified, and their shouts prevailed. Pilate released Barabbas and handed over Jesus to be scourged and crucified.

Initially rejected Jesus because Jesus was from Nazareth but acknowledged him as the “Son of God” and “King of Israel” when they met. He was Tortured & Crucified in India.

As Jesus was walking by him, Bartimaeus heard who it was that was passing and called out to Him: Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me! By calling Jesus the Son of David, the blind man was affirming his belief that Jesus was the Messiah.

The people told Bartimaeus to be quiet, but he kept calling out, even more loudly and persistently than before. This is further proof of his faith. In addition to his proclamation of Jesus’ identity as the Messiah, the blind man showed that he believed in Jesus’ goodness and deference to the poor and needy.

Bartimaeus believed that Jesus was not like the other religious leaders, who believed that an individual’s poverty or blindness or bad circumstances were a result of God’s judgment.

Jesus responded to Bartimaeus’s cries by telling His disciples to call the blind man over. Blind Bartimaeus jumped up and went to Jesus, and Jesus asked him, What do you want me to do for you? The beggar could have asked for money or for food, but his faith was bigger than that.

Bartimaeus said, Rabbi, I want to see. There is no pretention or religious pride in this interchange between God and man. The blind man had a desire, and he ran to Jesus with that desire.

He simply expressed to Jesus his desire, trusting that Jesus was both willing and able to fulfill it. Jesus said to him, Go your faith has healed you, and Blind Bartimaeus instantly recovered his sight and followed Jesus.

By saying, Your faith has made you well, Jesus emphasizes the necessity of faith. Blind Bartimaeus had the kind of faith that pleases God—a wholehearted trust in the Healer.

Jesus showed once again that God rewards those who earnestly seek him. Blind Bartimaeus understood this truth. He earnestly sought the Lord, and his actions reflected the kind of faith that is pleasing to God.

Bathsheba was the daughter of Eliam. Her father is identified by some scholars with Eliam mentioned as the son of Ahithophel, who is described as the Gilonite. Bathsheba was the wife of Uriah the Hittite, and afterward of David, by whom she gave birth to Solomon, who succeeded David as king.

David’s seduction of Bathsheba, is omitted in the Books of Chronicles. The story is told that David, while walking on the roof of his palace, saw Bathsheba, who was then the wife of Uriah, having a bath. He immediately desired her and later made her pregnant.

In an effort to conceal his sin, and save Bathsheba from punishment for adultery, David summoned Uriah from the army (with whom he was on campaign) in the hope that Uriah would re-consummate his marriage and think that the child was his. But Uriah was unwilling to violate the ancient kingdom rule applying to warriors in active service. Rather than go home to his own bed, he preferred to remain with the palace troops.

After repeated efforts to convince Uriah to have sex with Bathsheba, the king gave the order to his general, Joab, that Uriah should be placed on the front lines of the battle, where Uriah would be more likely to die. David had Uriah himself carry the message that led to his death. After Uriah was dead, David married the now widowed Bathsheba.

David’s action was displeasing to the Lord, who accordingly sent Nathan the prophet to reprove the king. After relating the parable of the rich man who took away the one little ewe lamb of his poor neighbor, and exciting the king’s anger against the unrighteous act, the prophet applied the case directly to David’s action with regard to Bathsheba.

The king at once confessed his sin and expressed sincere repentance. Bathsheba’s first child by David was struck with a severe illness and died, unnamed, a few days after birth, which the king accepted as his punishment. Nathan also noted that David’s house would be punished to avenge Uriah’s murder.

Bathsheba later gave birth to David’s son Solomon. David’s punishment came to pass years later when one of David’s much-loved sons, Absalom, led an insurrection that plunged the kingdom into civil war.

Moreover, to manifest his claim to be the new king, Absalom had sexual intercourse in public with ten of his father’s concubines, which could be considered a direct, tenfold divine retribution for David’s taking the woman of another man.

In David’s old age, Bathsheba secured the succession to the throne by Solomon, her son with David, according to David’s earlier promise, instead of David’s elder surviving sons by other wives, such as Kileab, Adonijah and others.

Belshazzar was the last king of ancient Babylon and is mentioned in Daniel 5. Belshazzar reigned for a short time during the life of Daniel the prophet. His name, meaning “Bel protect the king,” is a prayer to a Babylonian god; as his story shows, Bel was powerless to save this evil ruler.

Belshazzar ruled Babylon, a powerful nation with a long history and a long line of powerful kings. One of those kings was Nebuchadnezzar, who had conquered Judah, bringing the temple treasures to Babylon along with Daniel and many other captives. Belshazzar was Nebuchadnezzar’s grandson through his daughter Nitocris. Belshazzar calls Nebuchadnezzar his “father” in Daniel 5:13, but this is a generic use of the word father, meaning “ancestor.”

During his life, King Nebuchadnezzar had encountered the God of Israel’s power and was humbled by Him, but twenty years after Nebuchadnezzar’s death, his grandson Belshazzar praised the gods of gold and silver, of bronze, iron, wood and stone.

One fateful night in 539 BC, as the Medes and the Persians lay siege to the city of Babylon, King Belshazzar held a feast with his household and a thousand of his noblemen.

The king demanded all the gold and silver cups and vessels plundered from the Jewish temple be brought to the royal banquet hall. They filled the vessels with wine and drank from them, praising their false gods.

The use of the articles from the Jewish temple was a blasphemous attempt for Belshazzar to relive the glory days of his kingdom, to recall the time when Babylon was conquering other nations instead of being threatened with annihilation from the Persians outside their walls.

As the drunken king reveled, God sent him a sign: a human hand appeared, floating near the lampstand and writing four words in the plaster of the wall: “MENE MENE TEKEL PARSIN.” Then, the hand disappeared.

The king paled and was extremely frightened; he called his wise men and astrologers and enchanters to tell him what the writing meant, promising that whoever reads this writing and tells me what it means will be clothed in purple and have a gold chain placed around his neck, and he will be made the third highest ruler in the kingdom. But none of the wise men of Babylon could interpret the words.

Hearing a commotion in the banquet hall, the queen (possibly Nitocris or even Nebuchadnezzar’s widow) came to investigate. She remembered Daniel as one whose wisdom Nebuchadnezzar had trusted, and she told Belshazzar to summon the Jewish prophet.

Daniel was brought before the king, but he refused the gifts Belshazzar offered him, the kingdom was not his to give, as it turned out. Daniel rebuked Belshazzar’s pride: although the king knew the story of how God humbled his grandfather, he did not humble himself. Instead, he dishonored God by drinking from the sacred items of the temple.

Then, Daniel interpreted the words on the wall. Mene means God has numbered the days of your kingdom and brought it to an end. Tekel means you have been weighed in the balances and found wanting. Parsin means your kingdom is divided and given to the Medes and Persians. Daniel never revealed what language those words belong to.

That night, the Persians invaded. Cyrus the Great, king of Medo-Persia, broke through the supposedly impenetrable wall of Babylon by cleverly diverting the river flowing into the city so that his soldiers could enter through the river duct.

Historical records show that this invasion was made possible because the entire city was involved in a great feast—the feast of Belshazzar mentioned in Daniel 5. That very night Belshazzar, king of the Babylonians, was slain, and Darius the Mede took over the kingdom.

Benaiah was inspired by a noble ambition. He came of a noble ancestry, whose forefathers had left their impress upon the history of the nation. Born well, Benaiah sought to live well.

Absalom became a traitor to his godly father and broke his heart. The sons of priestly Eli lived in sin and died in disgrace. Benaiah, privileged with the example of godly parentage, looked upon life as a challenge to personal and individual responsibility.

He was fearless in his destruction of Israel’s foes. Born in an age of warfare, when youths were valiant in fight and middle-aged men were veterans, Benaiah had been valiant in many a campaign against hostile nations.

This grandson of a valiant man of Kabzeel had many mighty deeds to his credit. Three glimpses are given of Benaiah’s bravery. He confronted two lionhearted men of Moab—giants among their fellows—either of whom would have been more than a match for any ordinary soldier; but Benaiah took them both on and was the victor.

Then he attacked the Egyptian of “great statute” but although this dark-skinned giant carried a spear “like a weaver’s beam” Benaiah met him with an ordinary staff and left the field victorious.

Benaiah’s next exploit finds him attacking not “lionhearted men” but an actual lion that had alarmed the people. A pit was dug to trap the marauding lion, and snow fell and hid the trap in a most effective way. The lion fell into the pit and vainly tried to extricate itself.

Benaiah, the hero who had vanquished a giant and conquered two lionhearted Moabites, descended the pit on a snowy day and single-handed slew the lion. No wonder David, who also had slain a lion, gave Benaiah the chief place among the favored three.

In the Old Testament, the second son of Jacob and Rachel.

Jacob blessed Benjamin. The descendants of Benjamin were a warlike race. Two important Benjamites were Saul, the first Israelite king, and Paul, the New Testament Apostle.

The name “Bezalel” means “in the shadow of God.” Bezalel is described in the genealogical lists as the son of Uri, the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah.

He was said to be highly gifted as a workman, showing great skill and originality in engraving precious metals and stones and in wood-carving. He was also a master-workman, having many apprentices under him whom he instructed in the arts.

According to the narrative in Exodus, he was called and endowed by God to direct the construction of the tent of meeting and its sacred furniture, and also to prepare the priests’ garments and the oil and incense required for the service. He was also in charge of the holy oils, incense and priestly vestments. Caleb was his great-grandfather.

The rabbinical tradition relates that when God determined to appoint Bezalel architect of the desert Tabernacle, He asked Moses whether the choice were agreeable to him, and received the reply: “Lord, if he is acceptable to Thee, surely he must be so to me!” At God’s command, however, the choice was referred to the people for approval and was endorsed by them.

Moses thereupon commanded Bezalel to set about making the Tabernacle, the holy Ark, and the sacred utensils. It is to be noted, however, that Moses mentioned these in somewhat inverted order, putting the Tabernacle last.

Bezalel sagely suggested to him that men usually build the house first and afterward provide the furnishings; but that, inasmuch as Moses had ordered the Tabernacle to be built last, there was probably some mistake and God’s command must have run differently.

Bezalel possessed such great wisdom that he could combine those letters of the alphabet with which heaven and earth were created; this being the meaning of the statement: “I have filled him with wisdom and knowledge,” which were the implements by means of which God created the world.

By virtue of his profound wisdom, Bezalel succeeded in erecting a sanctuary which seemed a fit abiding-place for God, who is so exalted in time and space.

The candlestick of the sanctuary was of so complicated a nature that Moses could not comprehend it, although God twice showed him a heavenly model; but when he described it to Bezalel, the latter understood immediately, and made it at once; whereupon Moses expressed his admiration for the quick wisdom of Bezalel, saying again that he must have been “in the shadow of God” when the heavenly models were shown him.

Bezalel is said to have been only thirteen years of age when he accomplished his great work; he owed his wisdom to the merits of pious parents; his grandfather being Hur and his grandmother Miriam, he was thus a grandnephew of Moses.

The son of Rahab (who may be Rahab of Jericho) and Salmon, Boaz was a wealthy landowner of Bethlehem in Judea, and kinsman of Elimelech, Naomi‘s late husband.

He noticed Ruth, the widowed Moabite daughter-in-law of Naomi, a relative of his, gleaning grain in his fields. He soon learns of the difficult circumstances her family is in and Ruth’s loyalty to Naomi. In response, Boaz invites her to eat with him and his workers, as well as deliberately leaving grain for her to claim while keeping a protective eye on her.

Ruth approaches Boaz and asks him to exercise his right of kinship and marry her. Boaz accepts, provided that another with a superior claim declines. Since the first son of Ruth and a kinsman of her late husband would be deemed the legal offspring of the decedent and heir to Elimelech, the other kinsman defers to Boaz.

In marrying Ruth, Boaz revives Elimelech’s lineage, and the patrimony is secured to Naomi’s family. Their son was Obed, father of Jesse, and grandfather of David. According to Josephus, he lived at the time of Eli.

The story of Caleb, a faithful man of God, begins in the book of Numbers. After being delivered from bondage in Egypt, the Israelites were led by God to the border of the land of Canaan, a land “flowing with milk and honey” that God had promised they would inherit.

Moses had chosen twelve men, one from each tribe, to scout the land before entering. Among them was Caleb, representing the tribe of Judah. The twelve men spied out the land for forty days and then came back to Moses.

They reported that the land was indeed fruitful but its inhabitants were the mighty descendants of Anak. Terrified by the size and strength of the Canaanites, ten of the spies warned Moses not to enter Canaan.

Caleb silenced the murmuring, fearful men by saying, “We should go up and take possession of the land, for we can certainly do it”. Caleb took his stand because he followed the Lord wholeheartedly.

Caleb knew of the promises of God to the Israelites, and, despite the evidence of his own eyes regarding the obstacles, he had faith that God would give them victory over the Canaanites.

Unfortunately, the people of Israel ignored Caleb and listened to the report of the other spies. They were so frightened that they wept all night and even wished they had died at the hands of their slave masters in Egypt. They turned on Caleb and Joshua (the spy from Ephraim) and wanted to stone them on the spot.

God was exceedingly angry with the people and threatened to destroy them until Moses interceded for them. God relented, but He decreed that the people would wander in the wilderness until all of that faithless generation had died. But God said that “my servant Caleb has a different spirit and follows me wholeheartedly” and gave him the promise that he would own all the land he had seen as a spy.

The Israelites wandered in the wilderness for forty years until all of that generation, except Joshua and Caleb, died. After the forty years of wandering and five more years of war within Canaan, Caleb was 85 years old; yet he was as strong as ever and able to fight the same Anakites that had frightened his countrymen. His confidence was born out of his absolute faith in the promises of God.

Caleb’s territory in Canaan included “Kiriath Arba, that is, Hebron. (Arba was the forefather of Anak.) From Hebron Caleb drove out the three Anakites—Sheshai, Ahiman and Talmai, the sons of Anak. From there he marched against the people living in Debir (formerly called Kiriath Sepher)”.

Othniel, a nephew of Caleb, captured Kiriath Sepher and was given Caleb’s daughter Aksah to wed. Later, Aksah asked her father to include some springs of water as part of her inheritance, and Caleb gave them to her. Later still, Othniel, Caleb’s son-in-law, became Israel’s first judge.

From the accounts of the life of Caleb, we see a faithful man who trusted God to fulfill His promises when others allowed their fears to override their small faith. Even into his later years, Caleb remained steadfast in his faith.

God blessed Caleb for his faithfulness and patience, an encouragement to us to believe God. Like Caleb, we should be prepared to follow God in every circumstance, patiently waiting for Him to fulfill His promises and ready to take action when the time is right.

High priest from A.D. 18 to A.D. 36; son-in-law of Annas, high priest A.D. 7–14. He belonged to the Sadducee party and took an active part in the attack made upon our Lord and His disciples.

Cain is the first child of Eve, the first murderer, and the first human being to fall under a curse. Cain treacherously murdered his brother Abel, lied about the murder to God, and as a result was cursed and marked for life.

With the earth left cursed to drink Abel’s blood, Cain was no longer able to farm the land. Cain is punished as a “fugitive and wanderer”.

He receives a mark from God, commonly referred to as the mark of Cain, representing God’s promise to protect Cain from being murdered.

The name of the fourth son of Ham; also used to denote the tribe inhabiting the lowland (hence the name) toward the Mediterranean coast of Palestine; sometimes as a general name for all the non-Israelite inhabitants of the country west of Jordan, called by the Greeks Phoenicians.

The Hebrew and Phoenician languages were almost identical. As the Phoenicians were great traders, Canaanite came to denote merchant.

Cyrus is a king mentioned more than 30 times in the Bible and is identified as Cyrus the Great (also Cyrus II or Cyrus the Elder) who reigned over Persia between 539—530 BC. This pagan king is important in Jewish history because it was under his rule that Jews were first allowed to return to Israel after 70 years of captivity.

In one of the most amazing prophecies of the Bible, Isaiah predicts Cyrus’ decree to free the Jews. One hundred fifty years before Cyrus lived, the prophet calls him by name and gives details of Cyrus’ benevolence to the Jews:

This is what the Lord says to his anointed, to Cyrus, whose right hand I take hold of to subdue nations before him. I summon you by name and bestow on you a title of honor, though you do not acknowledge. Evincing His sovereignty over all nations, God says of Cyrus, He is my shepherd and will accomplish all that I please.

King Cyrus actively assisted the Jews in rebuilding the temple in Jerusalem under Ezra and Zerubbabel. Cyrus restored the temple treasures to Jerusalem and allowed building expenses to be paid from the royal treasury.

Cyrus’s beneficence helped to restart the temple worship practices that had languished during the 70 years of the Jews’ captivity. Some commentators point to Cyrus’s decree to rebuild Jerusalem as the official beginning of Judaism.

Among the Jews deported from Judah and later placed under the rule of Cyrus include the prophet Daniel. In fact, we are told Daniel served until at least the third year of King Cyrus, approximately 536 BC.

That being the case, Daniel likely had some personal involvement in the decree that was made in support of the Jews. The historian Josephus says that Cyrus was informed of the biblical prophecies written about him. The natural person to have shown Cyrus the scrolls was Daniel, a high-ranking official in Persia.

Besides his dealings with the Jews, Cyrus is known for his advancement of human rights, his brilliant military strategy, and his bridging of Eastern and Western cultures.

He was a king of tremendous influence and a person God used to help fulfill an important Old Testament prophecy. God’s use of Cyrus as a shepherd for His people illustrates the truth of Proverbs 21:1, The king’s heart is in the hand of the LORD; he directs it like a watercourse wherever he pleases.

In the third year of the reign of Jehoiakim, Daniel and his friends Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah were among the young Jewish nobility carried off to Babylon following the capture of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon.

The four are chosen for their intellect and beauty to be trained in the Babylonian court and are given new names. Daniel is given the Babylonian name Belteshazzar, while his companions are given the Babylonian names Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-Nego.

Daniel and his friends refuse the food and wine provided by the king of Babylon to avoid becoming defiled. They receive wisdom from God and surpass all the magicians and enchanters of the kingdom. Nebuchadnezzar dreams of a giant statue made of four metals with feet of mingled iron and clay, smashed by a stone from heaven.

Only Daniel is able to interpret it: the dream signifies four kingdoms, of which Babylon is the first, but God will destroy them and replace them with his own kingdom.

Nebuchadnezzar dreams of a great tree that shelters all the world and of a heavenly figure who decrees that the tree will be destroyed; again, only Daniel can interpret the dream, which concerns the sovereignty of God over the kings of the earth.

When Nebuchadnezzar’s son King Belshazzar uses the vessels from the Jewish temple for his feast, a hand appears and writes a mysterious message on the wall, which only Daniel can interpret; it tells the king that his kingdom will be given to the Medes and Persians, because Belshazzar, unlike Nebuchadnezzar, has not acknowledged the sovereignty of the God of Daniel.

The Medes and Persians overthrow Nebuchadnezzar and the new king, Darius the Mede, appoints Daniel to high authority. Jealous rivals attempt to destroy Daniel with an accusation that he worships God instead of the king, and Daniel is thrown into a den of lions, but an angel saves him, his accusers are destroyed, and Daniel is restored to his position.

In the third year of Darius, Daniel has a series of visions. In the first, four beasts come out of the sea, the last with ten horns, and an eleventh horn grows and achieves dominion over the Earth and the Ancient of Days (God) gives dominion to one like a son of man.

An angel interprets the vision. In the second, a ram with two horns is attacked by a goat with one horn; the one horn breaks and is replaced by four. A little horn arises and attacks the people of God and the temple, and Daniel is informed how long the little horn’s dominion will endure. In the third, Daniel is troubled to read in holy scripture (the book is not named but appears to be Jeremiah) that Jerusalem would be desolate for 70 years.

Daniel repents on behalf of the Jews and requests that Jerusalem and its people be restored. An angel refers to a period of 70 sevens (or weeks) of years. In the final vision, Daniel sees a period of history culminating in a struggle between the “king of the north” and the king of the south in which God’s people suffer terribly; an angel explains that in the end the righteous will be vindicated and God’s kingdom will be established on Earth.

The book of Ezra mentions a king named Darius, also known as Darius I. He was the son of Hystaspes, the founder of the Persian dynasty. Darius I was king of Persia from 521 to 486 BC. His reign followed that of Cyrus the Great.

Darius I is presented as a good king who helped the Israelites in several ways. Prior to Darius’s reign, the Jews who had returned from the Babylonian Captivity had begun rebuilding the temple in Jerusalem.